Refractive Error (RE) is the leading cause of blindness globally (Jeganathan et al, 2017). Uncorrected Refractive Error (URE) affects academic performance, productivity, and quality of life (Wadhwani et al, 2020). Mannava et al (2022) estimated the economic burden of blindness in India and recommended that early detection and treatment of avoidable blindness, especially among children, is very important at all levels of primary health care.

A systematic review and meta-analysis in India reported that an overall prevalence of RE per 100 children was 8, and in schools it was 10.8. Combined RE and myopia alone were higher in urban areas and among girls in the school population (Sheeladevi et al, 2018). With the majority of the schools in urban areas in India, it is imperative that school-based visual acuity (VA) screening is vital for early detection of visual impairment. Johnson et al (1983) highlight school nurses' role in vision screening, follow-ups, and referrals. In India, though there is a mention of the ‘school nurse’ post/position, every school does not have a full-time school nurse (Purohit et al, 2024; Dhakshayani, 2023; MOE, 2021). Currently, the school eye health promotion activities are delivered through the school teachers or the Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) team (Jakasania et al, 2023). However, efforts are being made to train nurses in India for the roles of school health nurses. The Indian Nursing Council (INC) circular dated 26 May 2023 upholds undergraduate nursing students' involvement in school health checkups as a part of RBSK. Further, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in India expects Community Health Officers (CHOs) at the Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) to screen the population using Snellen’s chart. Nurses with BSc Nursing qualifications are eligible for the position of CHO.

Need of the study: If the magnitude of blindness and RE in India is to be reduced, early detection of visual impairment and its management must occur during childhood. School is an important location for screening of VA and for convincing the parents of the importance of preserving vision. The review of literature reveals that most of the published studies on visual impairment in India are by medical professionals. This is the first study in Madhya Pradesh involving a trained nurse in assessing the prevalence of visual impairment among secondary school students. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of trained graduate nurses in conducting RE screening, making early referrals and providing advice on eye health promotion at the schools.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were: (1) to assess the prevalence of RE among secondary school students in Bhopal District; (2) to identify the factors associated with RE among secondary school students.

Review of literature

Visual acuity is a fundamental measure of the eye's ability to distinguish shapes and fine details at a specified distance. VA assessment is essential in eye care to monitor changes over time and diagnose conditions such as RE, cataracts, corneal and retinal diseases and to evaluate the efficacy of treatments or interventions, such as corrective lenses or surgery. Timely diagnosis based on VA testing improves quality of life and can prevent further vision loss. VA is commonly tested using a multi-letter Snellen’s E chart, measured at a distance of six meters (Marsden J, 2014). When VA of 6/6 (normal vision) is not achieved, a pinhole occluder is used to verify if the vision improves or not. Improvement indicates that the vision impairment is due to the irregularities in the cornea or a RE, which is correctable with spectacles or a new prescription (McCormick et al, 2019). Based on the review, RE in this study was operationally defined as the VA of <6/9, in any one eye, assessed using a Snellen's E chart placed 6 metres away. Uncorrected refractive error (URE) was considered present when VA improved with the pinhole.

The prevalence of RE can be seen globally among school going children (Guan et al, 2019; Grzybowski, 2020; Fang et al, 2024; Atlaw et al, 2022). Studies across India reveal the prevalence of refractive error among school-going children (Sheela Devi et al, 2018; Saxena et al, 2019; Kerkar et al, 2020; Joseph et al, 2022). These studies reveal risk factors for different types of refractive errors, such as myopia, astigmatism, and anisometropia, including age, increased near-work activities and reduced outdoor time, and use of digital devices. Review reveals that reducing blindness in India requires early detection and management, with schools playing a crucial role in RE screening and awareness of parents on the need for early correction of visual impairment.

Materials and Methods

Research design, setting, and the sample: This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Bhopal district of Madhya Pradesh, India, in 2024. The estimated sample size at a 95 percent confidence level, considering the expected prevalence of 7 percent (Singh et al, 2013) and the precision of 3 percent was 277. Cluster sampling (single stage) was used in the study.

There were a total of 701 higher secondary schools in Bhopal district (565 private and 136 government). Permission was obtained from the Directorate of Education of Bhopal district; 15 schools were selected randomly (lottery method). Out of the 15, two schools refused permission. Adolescents (up to 19 years) studying in 9 to 12 standards, able to communicate in Hindi or English, available on the day of data collection and having provided informed consent (if above 18 years) or assent and informed consent from one of the parents, were included. The required sample size was reached with data collection in five schools.

Data Collection Instruments

a) Background proforma, with two sections: Socio-demographic data, and Clinical variables. The proforma was translated (forward and backwards) into the Hindi language by bilingual experts.

b) Snellen’s E chart, inch-tape and the pinholeoccluder, calibrated at Hi-Tech Laboratory.

c) Recording form and Referral form including personal identification details, VA findings, and advice written to visit an ophthalmologist at the earliest.

To ensure the reliability of Snellen’s chart and pinhole-occluder, VA was assessed among 25 college students using the calibrated Snellen's chart at first, followed by the standard Snellen's chart available at the tertiary health centre in Bhopal. The readings obtained in both assessments were compared. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient was 0.92.

Procedure of data collection: The investigator, an MSc (N) student a certified VA assessor, first sought permission from the school Principal, and explained the purpose of study to the students of classes 9 to 12. Confidentiality and anonymity of data were assured. The students below 18 years were instructed to explain the study to their parents (participant information sheet was provided) and seek informed consent from parents.

Next day, the eligible participants were administered a background proforma in their respective classrooms. VA was assessed individually in a separate classroom with proper illumination. The Snellen’s chart was fixed on the wall at 6 meters (measured using the inch tape). Each eye was assessed (better eye first). For those using spectacles, VA was first assessed without spectacles, followed by with spectacles. VA was re-assessed with a pinhole occluder in the eye(s) with VA <6/9. Readings were documented in the recording form. Eye health promotion advice was given and documented. Referral form was initiated if VA improved with the pinhole-occluder test and was given to the participant with advice to see the Ophthalmologist at the earliest, and show the referral form to the parents. The list of participants referred to the Ophthalmologist was also given to the school Principal.

Results

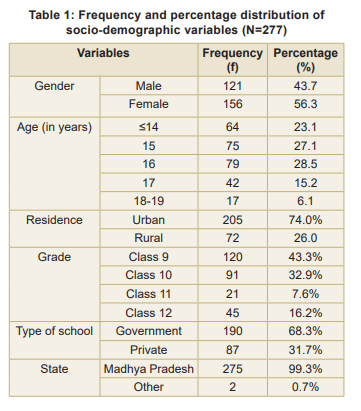

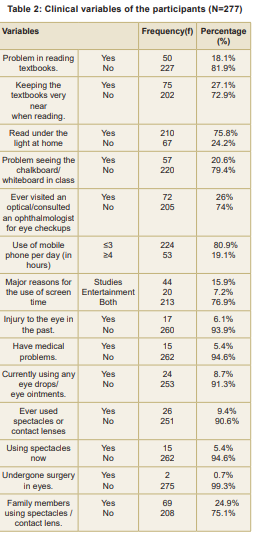

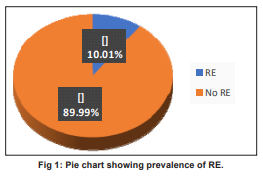

Data was analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 20. Tables 1 and 2 describe the participant characteristics. Of the 28 participants (10.1%) had RE (Fig.), of whom 15 students used spectacles (corrected RE) and 13 participants (46.43%) did not. Among the 15 using spectacles, five required further correction. Thus, a total of 18 participants were referred to the Ophthalmologist.

RE was associated with gender [χ2=13. 762 (df=1), p<0.001], residence [χ2 =8.140 (df=1), p< 0.003], type of school (χ2 =12.418 (df=1), p<0.001], problems in reading textbook [χ2 =38.843 (df=1), p<0.001], seeing the chalkboard or whiteboard in class [χ2 =72.239 (df=1), p<.001], keeping the book very near when reading [χ2 =21.843 (df=1), p<0.001], light source at home [χ2 =72.239 (df=1), p<.001], visiting optical clinics/ophthalmologist [χ2 =15.587 (df=1), p<0.001), having medical problems [χ2 =15.595 (df=1), p=0.002], history of ever using spectacles/contact lens [χ2 =79.378 (df=1), p<0.001], and using spectacles now [χ2 =141.03 (df=1), p<0.001]. RE was not associated with the rest of the variables (Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

The findings indicate that RE is prevalent among secondary school children in Bhopal. Nearly half of their visual impairment is not corrected, and about one-third of the participants with corrected RE require further correction. The findings reveal that only a quarter of the students visit for eye check-ups. With a habit of using digital devices (for studies or entertainment) as well as increased use of technology in the education today in teaching and learning, visual impairment among children will continue to rise (Joseph et al, 2023), who found that RE, especially myopia, is common in India. Its prevalence varied across regions in India (1.09% to 6.08%) among schoolgoing children (5-18 years). The lesser prevalence of RE in Madhya Pradesh (3.06%) is attributable to the reason that the majority of the participants in the study were from rural/semi-urban, and the parents’ literacy rate was comparatively lower. However, a study in Madhya Pradesh (Balke et al, 2023) reported a prevalence of 11.3 percent among 5 -15-year-old children.

While Balke et al (2023) observed uncorrected myopia mostly among 13-15-year-olds, Joseph et al (2023) found that myopia risk was higher among female and private school children of urban areas. Fang et al (2024) reported near-work activities and reduced outdoor time as risk factors for myopia, astigmatism, and anisometropia. Guan et al (2019) reported significant associations between RE and prolonged computer (>60 minutes/day, -0.025 LogMAR, p= 0.011) and smartphone use (-0.041 LogMAR, p = 0.001). In contrast, watching television and after-school study showed no such link. No association was found between mobile phone usage and RE in the present study, which could be because the majority of participants were studying in government schools, where technology usage in teaching and learning activities was very limited at the time of this study. The education system in Madhya Pradesh is undergoing reform with the introduction of technology in recent times, and thus, the association needs to be reassessed in similar studies in the future.

Vision screening in this study was conducted by a trained nurse, underscoring the role of nurses and CHOs in India in school-based screening. Johnson et al. emphasised the critical role of nurses in vision screening, referrals, and follow-ups. Despite the absence of full-time school nurses, CHOs can extend vision screening services annually and refer students to the RBSK team. This approach would aid universal health care coverage by the CHO. Staff nurses in RBSK teams may also conduct VA assessments. This study demonstrates that school-based VA screening is feasible, as the required equipment is portable, reusable, and arrangements for assessment at school can be made within the available space. Nursing implications: Eye health screening at the schools is essential, and trained nurses from can organise eye screening camps in collaboration with the education sector to help identify defects or disorders in school-going populations and also provide opportunities for nursing students to practice their clinical skills. A follow-up of students with RE may be scheduled to determine whether they have consulted the ophthalmologist. Such involvement can be extended to VHSND held at the HWC level. Nursing Colleges must integrate their services with the peripheral health centres or in collaboration with the District Health Office.

Nursing implications: Eye health screening at the schools is essential, and trained nurses from can organise eye screening camps in collaboration with the education sector to help identify defects or disorders in school-going populations and also provide opportunities for nursing students to practice their clinical skills. A follow-up of students with RE may be scheduled to determine whether they have consulted the ophthalmologist. Such involvement can be extended to VHSND held at the HWC level. Nursing Colleges must integrate their services with the peripheral health centres or in collaboration with the District Health Office.

Recommendation

A similar study could be conducted among school dropout adolescents, and the results may be compared with those enrolled in schools. This may help explore other factors associated with RE, if any. A study may be planned to train undergraduate nursing students in VA assessment and evaluate the effectiveness of the training against their performance as a nursing intern/nursing officer, or a CHO.

Conclusion

This study found a 10.01 percent prevalence of RE among school students in Bhopal. RE was associated with gender, residence, school type, reading difficulties, proximity while reading, board visibility issues, and spectacle use. VA assessment at the school premises by trained nurses is feasible and can be viewed as a measure of inter-sectoral coordination between nursing training institutions and the education sector. VA screening by trained nurses should be viewed as a cost-effective primary health care measure (to detect visual impairment at an early age and refer for corrections) by the decision makers.

1. Jeganathan VSE, Robin AL, Woodward MA. Refractive error in underserved adults: Causes and potential solutions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2017 Jul; 28(4): 299–304. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000376

2. Wadhwani M, Vashist P, Singh SS, Gupta V, Gupta V, Gupta N et al. Prevalence and causes of childhood blindness in India: A systematic review. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020 Feb; 68 (2): 311-15. Available from: https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31957718/

3. Mannava S, Borah RR, Shamanna BR. Current estimates of the economic burden of blindness and visual impairment in India: A cost of illness study. Indian J Ophthalmol 2022; 70: 21415. Available from: https://doi.org/10..4103/ijo. IJO_2804_21

4. Purohit BM, Malhotra S, Burma MD, Bhadauria US, Agarwal D, Shivakumar S, et al. Effectiveness of an oral health promotion training program among school nurses in India. Nurse Educ Today. 2024 Jan 1; 132: 105989. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37913634/

5. Dhakshayani TD. Forgotten voices: The onerous role of school health nurses in residential schools of India – a viewpoint. J Appl Nurs Health 2023; 5(2): 307-14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.55018/janh.v5i2.162

6. Jakasania A, Lahariya C, Pandya C, Raut AV, Sharma R,K S et al. School health services in India: status, challenges and the way forward. Indian J Pediatr 2023 Sep; 90 (Suppl 1):116–124. doi: 10.1007/s12098-023-04852-x

7. Marsden J, Stevens S, Ebri A. How to measure distance visual acuity. Community Eye Health J 2014; 27 (85): 16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/24966459/

8. McCormick I, Mactaggart I, Bastawrous A, Burton MJ, Ramke J. Effective refractive error coverage: An eye health indicator to measure progress towards universal health coverage. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2019 Dec 26; 40 (1): 1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12662

9. Guan H, Yu NN, Wang H, Boswell M, Shi Y, Rozelle S, et al. Impact of various types of near work and time spent outdoors at different times of day on visual acuity and refractive error among Chinese school-going children. PloS One 2019 Apr 26; 14 (4): e0215827. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215827

10. Grzybowski A, Kanclerz P, Tsubota K, Lanca C, Saw SM. A review of the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide. BMC Ophthalmol 2020 Jan 14; 20 (1): 27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-019- 1220-0 11. Fang XH, Song DS, Jin N, Du B, Wei RH. Refractive errors in Tianjin youth aged 6–18 years: exploring urban–rural variations and contributing factors. Front Med 2024 Sep17;

11: 1458829. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/ fmed.2024.1458829

12. Singh H, Saini VK, Yadav A, Soni B. Refractive errors in school-going children: Data from a school screening survey programme. Natl J Community Med 2013; 4(1): 137-40. Available from: https://njcmindia.com/index.php/ file/article/view/1478

13. Atlaw D, Shiferaw Z, Sahiledengele B, Degno S, Mamo A. Prevalence of visual impairment due to refractive error among children and adolescents in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2022 Aug 18; 17(8): e0271313. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0271313

14. Saxena A, Nema N, Deshpande A. Prevalence of refractive errors in school-going female children of a rural area of Madhya Pradesh, India. J Clin Ophthalmol Res 2019. May 1; 7(2): 45. Available from: https://journals.lww. com/jcor/fulltext/2019/07020/prevalence_of_refractive_errors_in_school_going.4.aspx

15. Kerkar S, Apurva T. An observational study to evaluate the prevalence and pattern of refractive errors in children aged 3-17 years in Mumbai, India. Int J Contemp Pediatr 2020; 7 (5): 1028. DOI:10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20201632

16. Joseph E, Ck Meena, Kumar Rahul, Sebastian M, Suttle CM, Congdon N, Sethu S, Murthy GV; REACH Research Group. Prevalence of refractive errors among school-going children in a multistate study in India. Br J Ophthalmol 2023; 108 (1): 143-51. Available from: https://pubmed. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36562766/

17. Balke M, Karole C, Varandani S. Prevalence of refractive error in school-going children in east Nimar (M.P). Int J Life Sci Biotechnol Pharma Res 2023 Jul-Sep; 12(3): 119- 23

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.