The facilities of the health care are consistently connected with a possible range of protection problems worldwide. Patients continue to be exposed to unintended harm in hospitals regardless of advancements in the health care system. The Health-associated Infection Prevalence Survey states that care- associated infections (HCAIs) exist in at least 1 in 31 hospitalised patients (CDC, 2024). It is the Health Care Workers (HCWs) who incessantly have contact with the patients by paving the way for the microorganisms to be spread by their hands (Bakarman et al, 2019). Non-compliance with Hand Hygiene (HH) is a significant problem in healthcare. It is the solitary, economical and realistic measure to narrow down the incidence of HCAI. The majority of infections occur as a consequence of hospitalisations. It affects roughly 5 to 10 percent among hospitalised patients in the developed countries, and the weight is increased in developing countries (Al Kadi & Salati, 2012). Multiple studies from India have indicated that HH compliance ranges from 20-85.5 percent. Another bundle of studies has shown that as low as 8 percent to as high as 85 percent related to HH compliance (Tyagi et al, 2018). A systematic review from developed countries reported compliance rates as 30-40 percent in ICUs (Erasmus et al, 2010).

Need for the study: The universal prevalence rate of HCAI ranges from 5.1 to 11.6 percent in developed countries and roughly 15.6 percent in developing countries. WHO reports that available evidence demonstrates that adherence with hand hygiene recommendations during health care delivery remains deficient around the world, with an average of 59.6 percent adherence levels in intensive care units up to 2018, and marked differences between high- and low-income countries (64.5% vs 9.1%) (Lambe et al, 2019). Studies conducted at various periods of time postulate that the average HH adherence in the absence of specific interventions was 40 percent till 2009 and 41percent between 2014 and 2020 (Clancy et al, 2021). Retaining genuine HH is an easy and economical method to prevent HCAIs. It not only decreases the rate of HCAIs but also forms an important representation of infection control programmes (Geraei et al, 2019).

Review of Literature

Various studies have demonstrated that adherence to HH enhances health and safeguards patients, decreases complications and duration of hospitalisation and death rate as well (Richards et al, 2014). The World Health Organisation’s survey manifested that adherence to HH among HCWs is smaller than 50 percent and shorter than 10 percent in hospitals with a huge workload (Hazavehei et al, 2016). And HH adherence is around 4 percent worldwide. The vital intervention tactics in the prevention of infection control among nurses are the HH. It creates a broadly accepted mainstay for the prevention of hospital-acquired infection (Vermeil et al, 2019). This is greatly supported by the WHO 2020. In the majority of cases, it is believed that infection is transmitted to patients through the hands of HCWs while caring for patients (Khodadadi, 2019).

An institutional based cross-sectional study was carried out by the health care providers. Out of 335 participants, 14.9 percent had good HH compliance. Training on HH (AOR= 8.07), availability of adequate soap and water for HH (AOR= 5.10), availability of alcohol-based hand rub (AOR= 3.23), and knowledge about HH (AOR= 2.15) were factors associated with HH compliance (Engdaw et al, 2019).

Objectives

The study was carried out with the objectives to: (a) assess the knowledge, practice and resources for compliance scores on hand hygiene among health care workers, (b) correlate between knowledge, practice and resources for compliance scores on hand hygiene among health care workers, and (c) associate the level of knowledge, practice and resources for compliance on hand hygiene with selected demographic variables.

Methodology

The research design adopted for the present study was a descriptive survey using quantitative approach. The target population of the study was health care workers. The ethical clearance was solicited from the Institutional Research Advisory Committee. Around 10 health care organisations were approached across India seeking permission.

Access to those organisations was carried out through a snowball approach. The four organisations which responded within the given time were Chirayu Medical College & Hospital, Bhopal; St Francis Hospital & Research Centre, Indore; Fortis Hospital, Kolkata & KVM College of Nursing, Kerala. The tool was prepared by the investigator with the help of an extensive literature search, and it was validated by experts. The tool was prepared in the shape of a Google form. The generated Google link was shared with the Heads of the health care organisations who shared the link with the participants. Participants who were willing completed the self-reports. The sampling technique solicited was the snowball method of non-probability type. The tool utilised for this study had following sections: demographic variables; Section A including items related to resources for hand hygiene compliance (26 items), with Yes/No response; Section B encompassing hand hygiene practice (30 items), with Yes/No response; and Section C including knowledge related to hand hygiene (8 items), with multiple choice questions. Anonymity of the data was ensured. The calculated sample size was 423. However, a total of 500 participants responded within the time frame. The tool was tested for reliability using Cronbach’s alpha for each section, and the values ranged from 0.81 to 0.86. The data was collected from July 2022 to June 2023.

Results

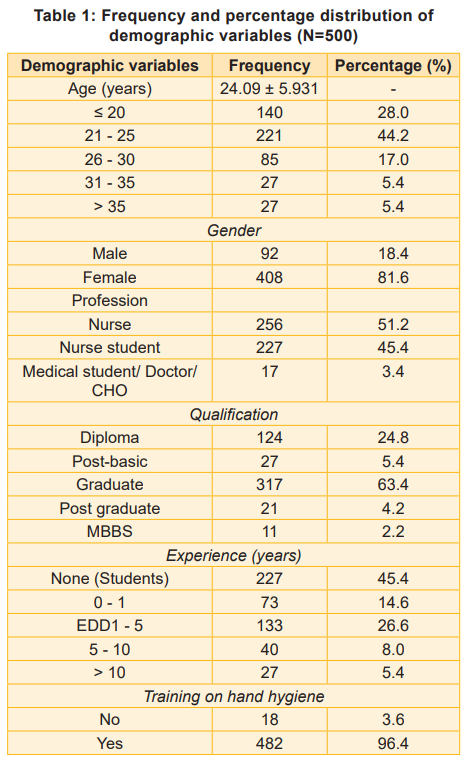

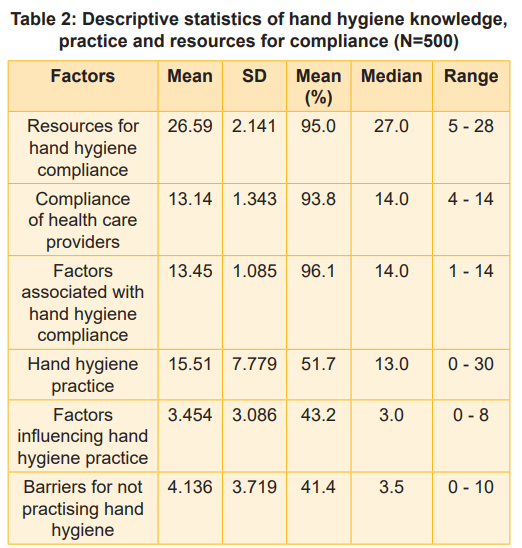

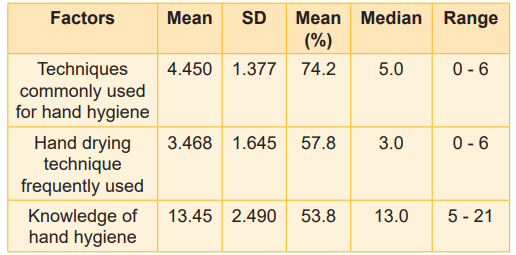

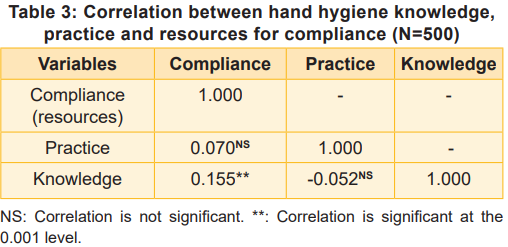

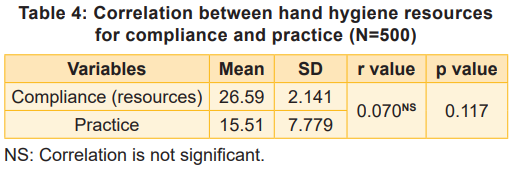

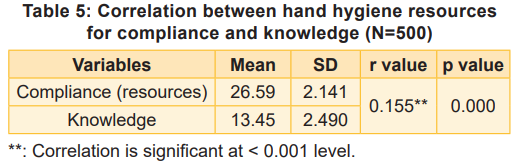

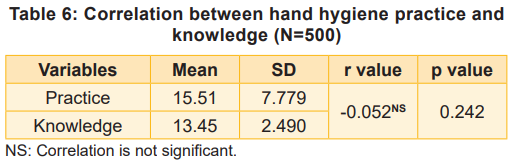

The data collected were analysed, corresponding to the objectives of the study, using descriptive and inferential statistics. The analysis was done using SPSS version 20.0. Table 1 depicts the demographic characteristics of the participants. The majority (44.2%) belonged to the age group 21-25 years; 81.6 percent were females; 50.2 percent were nurses; 62.6 percent were graduate; 37.2 percent had 1-5 years of experience, and 96.4 percent had undergone hand hygiene training. Table 2 depicts that 95 percent of the participants had hand hygiene resources for compliance, but 51.7 percent only practised hand hygiene, and 53.8 percent had knowledge on hand hygiene based on their self-reports. About hand hygiene compliance items, it meant regarding the availability of resources to practice hand hygiene in their facility. Table 3 shows that there was a significant correlation between resources for compliance and knowledge at p<0.001 level, whereas no correlation existed between resources for compliance and practice and knowledge and practice as well.

Correlations between hand hygiene resources for compliance and (a) practice and (b) knowledge are shown in Tables 4 and 5; Table 6 outlines the correlation between hand hygiene practice and knowledge.

The analysis further showed that there was no significant association except for hand hygiene compliance with profession, and hand hygiene practice with gender. Association was computed using ANOVA.

Discussion

HCAIs are highly alarming and remain a predominant cause of morbidity and mortality.

This study demonstrated that the mean percentage of hand hygiene practice was 51.7 percent, and knowledge was 53.8 percent. A cross-sectional study carried out among 924 participants revealed that the majority, 49.1 percent had poor knowledge in contrast to the present study (Dutta et al, 2020). Another cross-sectional study undertaken in the Alexandria University hospital among 236 health care workers found that the majority (55.8%) had a fair level of knowledge. A vast majority (91.3%) reported that hand hygiene practices were not practical in emergencies. Also, the most common barrier to hand hygiene practices reported was lack of sinks, soaps, paper towels and alcohol-based hand rubs (Salama et al, 2017), unlike the present study findings.

The present study findings projected that adequate resources were provided to the HCWs to practice hand hygiene (95%). Plenty of studies asserted that hand hygiene compliance was not followed for many reasons, and one major reason was a lack of resources. An observational study of hand hygiene compliance noted very low (6.8%) rate. Compliance was significantly scarce in the emergency room (1.0%), compared with the ICU (8.1%) (p = 0.0012), and the acute care ward (11.1%) (p < 0.0001) (Moued et al, 2021).

Recommendations Mixed-method research on the same topic may help to explore more reasons for not practising hand hygiene. Routine audits can be recommended to all hospitals to ensure that health care workers adhere to hand hygiene to an extent.

Nursing Implications

Knowledge and practice of hand hygiene are at a satisfactory level. However, compliance status requires availability of adequate resources to practice hand hygiene. Healthcare organisations should not only increase their endeavours by providing reinforcements for awareness and resources for practice, but also take disciplinary action at the administrative level in cases of negligence. This shall help prevent hospital-acquired infections on a large scale.

Conclusion

The study findings call for immediate intervention for promoting hand hygiene. It is not only the responsibility of the infection control of the hospital but also of the individual. Strict observation by the hospital team and regular audits should be a routine activity. The monitoring team should have representatives of the healthcare members, not nurses alone. The stronger the team and supervision, better the results may be. The lessons that the pandemic taught us should remain long-standing, and as healthcare workers, our focus should always be on primary prevention.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.