The majority of healthcare professionals are nurses and their skills considerably impact the standards of patient care (Brashers et al, 2016). Competency is a multifaceted, complex notion that includes mastery of specific skills, professional judgment and compliance to professional standards; clinical competency in nursing is a complex problem to solve (Rossler et al, 2019). Low competence levels may lead to decreased job satisfaction, increased professional disengagement, and decreased nursing care quality (Arakelian et al, 2017). On the other hand, being competent might alleviate burnout and build confidence among the nurses (Afshar et al, 2020). Clinical expertise is required for comprehensive nursing care in perioperative and high-dependency surgical units (Grey et al, 2017).

Nursing graduation programme confirms the development of fundamental skills related to perioperative competency-related clinical decision and analytical thinking (Erickson et al, 2016). High-end workshop training in surgical field ensures patient safety and serves as a foundation for improved perioperative nursing care competency to achieve quality patient care via cognitive, conative, and psychomotor abilities. We used participatory action research which assessed the impact of HEWON training (Karyashala) on development of nurses’ competency on modular operation theatres (Bays et al, 2014).

Healthcare requires interdisciplinary teamwork to improve the nurse’s performance, quality of patient care, and medical errors (Numasawa et al, 2021; Ajorpaz et al, 2016). Highend workshop training enabled nurses to update, promote, and coordinate their functions with swift adaptations (Bailey et al, 2014). Working together in a collaborative manner is challenging and diverse, with numerous challenges such as poor communication, lack of teamwork, role conflict, lack of problem-solving abilities, and inconsistencies that impede nurses from working together successfully and cause job dissatisfaction (Majda et al, 2021). The HEWON workshop training was organised in an effective collaboration in order to teach as well as to provide safe and competent nursing practice which facilitate to achieve quality outcome (Adell & Spruce, 2015; Adell MD, et al 2020; Ebrahimpour & Pelarak, 2016). The faculties from General Surgery, Anaesthesia, Orthopaedics, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Trauma, Emergency Care, and nursing conducted the training enhanced the knowledge and skill to handle the standard surgical equipment and instruments used in modular operation theatres. The six-day training programme gave participants hands-on experience surgical instruments, operation tables, lights, recording and transmission systems, and electrosurgical equipment (CUSA), which includes cleaning and sterilising surgical instruments to reduce the incidence of surgical site infections where they were trained by course facilitators.

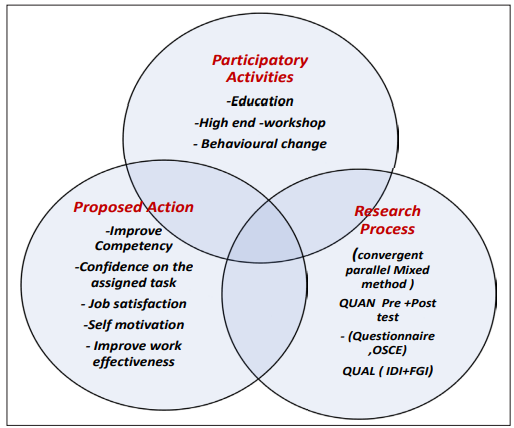

High-end workshop training and educational materials empowered nurses and supervisors, improving overall patient safety and work culture. In participatory action research (PAR), the mixed-methods design facilitated the nurses understanding of the situation and ensured that the study group could effectively modify their behaviour in challenging situations at Operative rooms (Mahdy & Mahfouz, 2016). To improve their performance and responsibilities, we taught the nurses specific competencies related to operation theatre techniques, thereby enhancing patient care in operative rooms. The conceptual framework employed is shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1: Conceptual framework of the participatory action research.

Materials & Methods

A convergent parallel mixed method design (QUAN+QUAL) was used to examine the competency of operating room nurses perioperative surgical nursing skills before and after attending HEWON workshop training (Mahdy et al, 2020). We employed a quasi-experimental design for quantitative approach. Purposive sampling method was used to recruit nurses with one year of clinical experience in the operation theatre; intervention group nurses had more than six months of experience in OT. The sample size was estimated based on Gostlow et al (2017) non-technical skills of surgical trainees and experienced surgeons in the British Journal of Surgery. The formula determined (n) α = 0.05%, β = 20% Power 80% with an estimated sample size of 40. Out of 50 participants recruited, 25 each were in experimental and control group. Registered nurses having not worked at OTs and those having undergone perioperative nursing care training were excluded. This study facilitated the participants to acquire and understand the essentials of basic and high-end surgical instruments used in modular OTs.

A three-part questionnaire was used to gather information: an objective structured clinical examination in the OT to evaluate psychomotor domain; feedback for participant satisfaction in HEWON training tested the participants’ level of knowledge with 29 multiple choice questions. Academic experts reviewed scientific texts to confirm the questionnaire’s validity. The reliability was calculated by estimating Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.92). SPSS 18 software collected and analysed the data. The p<0.001 level was used to determine statistical significance. One-way analysis of variance F-test and a student-independent t-test was used.

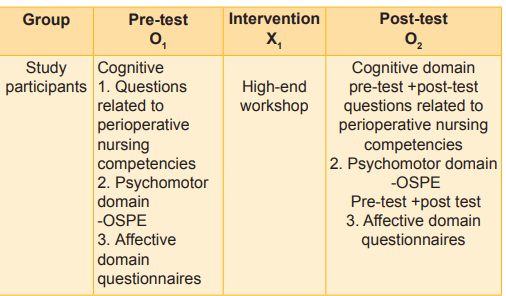

Table 1: Quasi-experimental design (QUAN)

For QUAL method in-depth interview and focused group interview are employed to evaluate the nursing perspectives and issues and challenges encountered by nurses in operating room (Table 1). Thematic content analysis was carried out using MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2020 software (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany) (Sergeeva et al, 2020). Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guideline was used. Participants were informed about the study and informed consent was obtained. The Ethics Committee, AIIMS Bhubaneswar, approved the protocol. The HEWON was funded by TNAI, New Delhi.

Results

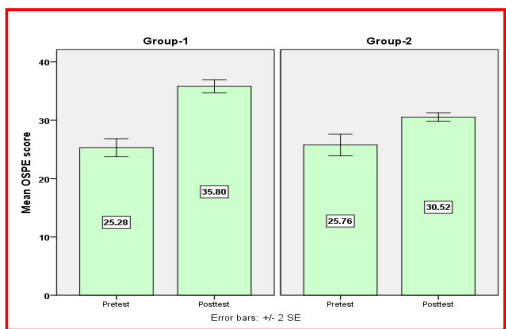

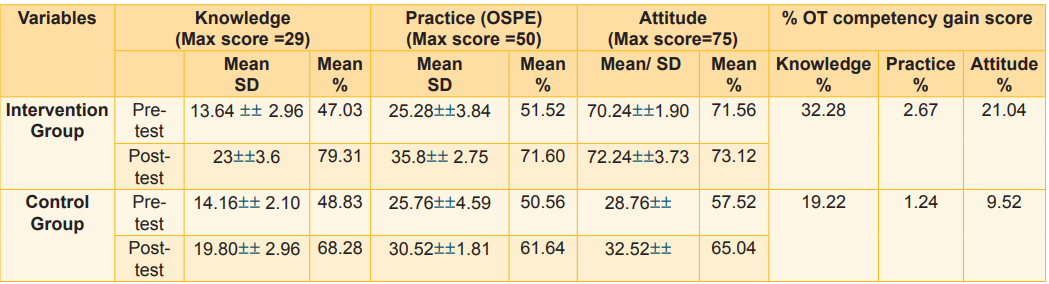

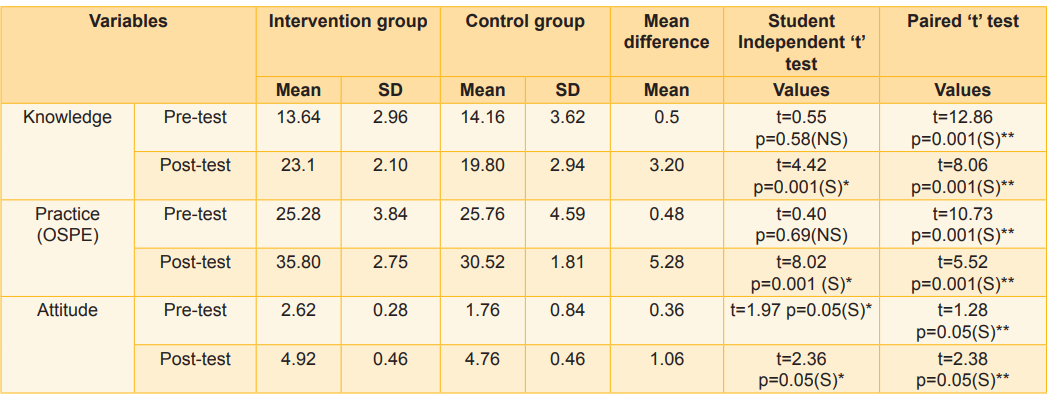

Fifty nurses attended the HEWON workshop, of whom 22 percent were male, and 68 percent female. Majority (94%) of the participants had never participated in an OT training workshop. More than half (64%) of participants were aged 22-27 years; 50 of the participants had 2 to 4 years of professional experience, of them 42 had less than one year experience; 86 percent of them were undergraduate nurses, and only 2 percent were postgraduate nurses. Table 1 shows that the knowledge mean score increased from 32.28 percent, the practice mean score was 2.67 percent, and attitude was 21.4 percent among the intervention group. Table 2 depicts the effectiveness of high-end workshop training on improving competency among OT nurses compared between intervention and control group. The knowledge, practice (OSPE), and attitude of nurses improved after attending the HEWON workshop. The nurses’ knowledge was enhanced from 13.64 ±± 2.96 (before training) to 23 ± 3.6 (after training) at t = 12.86 (p<0.001). Fig 2, the Objective Structured Practical Exam technique reveals a significant increase in nurses’ practice from 25.28 ± 3.84 (before training) to 35.8 ±± 2.75 (after training), with a substantial difference (t = 5.52, p = 0.001 level). The results indicated that nurses were either satisfied or more confident in modular OT techniques. The knowledge of nurses having more than 7-9 months of experience increased significantly (F = 4.73, p = 0.05) level after attending the HEWON workshop.

The overall experience and registration process of HEWON workshop was satisfied. The intervention group nurses reported a feedback score of 72.24, indicating a more learning experience than the control group’s score of 70.24. The difference was highly significant (t = 2.38, p = 0.05 level).

Fig 2: Bar diagram showing the effectiveness of HEWON training programme between the groups.

Table 2: Effectiveness of high-end workshop training among OT nurses (n=50)

Table 3: Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge, practice & attitude on perioperative nursing competency scores between the groups (n=50)

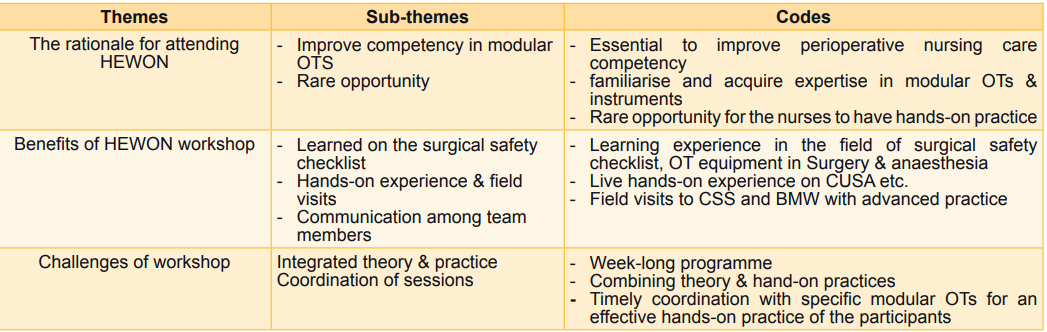

Table 4: Description of qualitative findings based on themes, subthemes & codes

Qualitative findings

Table 4 explains the themes, subthemes, and codes derived from thematic content analysis. The field notes were recorded during 25–35-minute semi-structured interviews. We analysed the data using systematic coding and theme development. This study examined the perceived advantages and need for a high-end workshop on perioperative surgical competencies among operating room nurses before and after training. All participants reported that HEWON training strengthened their perioperative competency, including surgical safety checklists, OT equipment and instruments, CSSD field visits, biomedical waste management measures, and intubation procedures, which facilitated to improve their operative nursing competency. Participants said the weeklong hands-on training was informative and unique. Communication between patients, anaesthetists, and surgeons was the most essential skill for OT nurses, HEWON training facilitated the learning experiences on communication, cooperation, safety, empathy, and critical thinking etc.

Discussion

The participatory action research investigated the impact of high-end workshop training on modular OT nurses’ competency. The HEWON workshop has improved the perioperative nursing competency among the nurses, the study findings are in par with those of Attari et al (2017). The educational session improved the competence among OT nurses, which is durable with continued practice in their setting. In-depth interviews revealed that participants recognised the impact of HEWON training programmes on peri-operative nursing competence despite needing access to them Uçak & Cebeci (2021) mentioned that certification helped nurses develop personally and professionally (Attari et al, 2017). High-end nurse workshop training optimises patient care with advanced OT nursing techniques. The evaluation of a high-end workshop on modular OT nursing competence showed substantial progress and ensured safe practice, the findings are corroborated by Colour et al (2021), who suggested that most crucial step in educational planning is assessment-based prioritisation. OT nurses should stay updated on new advancements and practices throughout their tenure. The PAR research found a favourable backdrop for nurses to participate in need-based competence training programmes for professional advancement (Rosenstein & O’Daniel, 2006).

The study’s outcome-driven suggestion is high-end workshop training for nurse promotion and empowerment. We also propose developing the HEWON module, a certified training programme with a few induction training components, to enhance the competence of novice nurses entering any healthcare institute overall. According to the findings of IDI, the investigators noted that HEWON training enhanced the clinical practice of nurses in operation theatres and offered valuable insights for developing an effective clinical teaching strategy in nursing education. These findings align with those of Sharif & Masoumi (2005).

Limitations

The participatory action study found that a weeklong high-end workshop training programme that incorporated theory and hands-on practices was challenging. The investigators faced challenges coordinating modular OTs during task schedules to ensure efficient hands-on practices and managing the logistics required for each task.

Conclusion

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of holding a high-end workshop in enhancing nurses’ competency in modular OTs. The study confirms that continuing education is essential for nurses to promote the quality of their care. Given the role and importance of professional factors, such as patient expectations from OT nurses, implementing continuing nursing education programme across institutes could enhance nurses’ professional knowledge. Credit hours based on conditioned attendance during the training period need to be considered for renewal of professional licensure.

1. Brashers V, Erickson JM, Blackhall L, Owen JA, Thomas SM, Conaway MR. Measuring the impact of clinically relevant interprofessional education on undergraduate medical and nursing student competencies: A longitudinal mixed methods approach. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2016 Jul; 30 (4): 448-57

2. Rossler KL, Sankaranarayanan G, Duvall A. Acquisition of fire safety knowledge and skills with virtual reality simulation. Nurse Educator 2019 Mar; 44 (2): 88

3. Arakelian E, Swenne CL, Lindberg S, Rudolfsson G, von Vogelsang AC. The meaning of person?centred care in the perioperative nursing context from the patient’s perspective–an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2017 Sep; 26 (17-18): 2527-44

4. Afshar M, Sadeghi-Gandomani H, Masoudi A N. A study on improving nursing clinical competencies in a surgical department: A participatory action research. Nursing Open 2020 Jul; 7(4): 1052-59

5. Grey C, Constantine L, Baugh GM, Lindenberger E. Advance care planning and shared decision-making: An interprofessional role-playing workshop for medical and nursing students. MedEdPORTAL 2017 Oct 18; 13: 10644

6. Gao L, Lu Q, Hou X, Ou J, Wang M. Effectiveness of a nursing innovation workshop at enhancing nurses’ innovation abilities: A quasi?experimental study. Nursing open 2022 Jan;9(1):418-27

7. Erickson JM, Brashers V, Owen J, Marks JR, Thomas SM. Effectiveness of an interprofessional workshop on pain management for medical and nursing students. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2016 Jul 3; 30 (4): 466-74

8. Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, Ford DW, Shannon SE, Downey Lois, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: Evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2014 Feb; 17 (2): 159-66

9. Numasawa M, Nawa N, Funakoshi Y, Noritake K, Tsuruta J, Kawakami C, et al. A mixed methods study on the readiness of dental, medical, and nursing students for interprofessional learning. Plos One 2021 Jul 22;16(7): e0255086

10. Ajorpaz NM, Tafreshi MZ, Mohtashami J, Zayeri F, Rahemi Z. The effect of mentoring on clinical perioperative competence in operating room nursing students. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2016 May; 25 (9-10): 1319-25

11. Bailey C, Hewison A. The impact of a ‘Critical Moments’ workshop on undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes to caring for patients at the end of life: An evaluation. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2014 Dec; 23 (23-24): 3555-63

12. Majda A, Zalewska-Pucha?a J, Bodys-Cupak I, Kurowska A, Barzykowski K. Evaluating the effectiveness of cultural education training: Cultural competence and cultural intelligence development among nursing students. Intern Journal Environ Res and Public Health 2021 Apr 11; 18(8): 4002

13. Adell White S, Spruce L. Perioperative nursing leaders implement clinical practice guidelines using the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice. AORN Journal 2015 Jul 1; 102 (1): 50-59

14. Adell MD, Galán MS, Ayora AF, Molina PS, Boira EJ. Specialized Training for Nursing in the Surgical Area, A Question of Quality. In: Contemporary Topics in Patient Safety-Vol 1, 2020 Oct 12. IntechOpen.94171

15. Ebrahimpour F, Pelarak F. Modified use of team-based learning to teach nursing documentation. Electronic Physician 2016 Jan; 8 (1): 1764

16. Mahdy AY, Mahfouz HH. Evaluate the effectiveness of nurses’ professional competence approach on their productivity in medical-surgical units. Egyptian Journal of Health Care 2016 Sep 1; 7(3): 271-91

17. Sergeeva MG, Shishov SE, Kalnei VA, Yulina GN, Polozhentseva IV. The development of professional competence of students in management training. Journal of Advanced Pharmacy Education & Research 2020; 10(1): 196-202

18. Mahdy AY, Mahfouz AC, Swenne CL, Gustafsson BÅ, Falk Brynhildsen K. Operating theatre nurse specialist competence to ensure patient safety in the operating theatre: A discursive paper. Nursing Open 2020 Mar; 7(2): 495-502

19. Swenne C. Operating theatre nurse specialist competence to ensure patient safety in the operating theatre: A discursive paper. Nursing Open 2019 Nov; 7 (2): 497-502. doi:10.1002/NOP2.424

20. Gostlow H, Marlow N, Thomas MJ, Hewett PJ, Kiermeier A, Babidge W, et al. Non-technical skills of surgical trainees and experienced surgeons. Br J Surg 2017 May; 104(6): 777-85. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10493. Epub 2017 Mar 13. PMID: 28295215

21. Jung JH, Kim HJ, Kim JS. Comparison of nursing performance competencies and practical education needs based on clinical careers of operating room nurses: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare (Basel) 2020 May 18; 8 (2): 136. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020136

22. Attari A, Aminoroaia M, Maracy MR. Efficacy of purposeful educational workshop of medical and nonmedical interventions based on needs assessments in nurses. J Educ Health Promot 2017 Apr 19; 6:18. doi: 10.4103/2277- 9531.204745. PMID: 28546983; PMCID: PMC5433647

23. Uçak A, Cebeci F. Competency in Operating Room Nursing: A Scoping Review. Journal of Education and Research in Nursing 2021 Sep 1; 18(3): 247-62

24. Getie A, Tsige Y, Birhanie E, Tlaye KG, Demis A. Clinical practice competencies and associated factors among graduating nursing students attending at universities in Northern Ethiopia: Institution-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021 Apr 1; 11(4): e044119

25. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Impact and implications of disruptive behaviour in the perioperative arena. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2006 Jul 1; 203(1): 96- 105

27. Grace PJ, Uveges M. Nursing ethics and professional responsibility in advanced practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2022 Aug 16

28. Sharif F, Masoumi Sara. A qualitative study of nursing student experiences of clinical practice. BMC Nurs 2005 Nov; Article No. 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-4-6

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.